Global China Academy and the National Academy of Chinese Modernization (NACM) at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Conduct Academic Exchanges and Study Visits

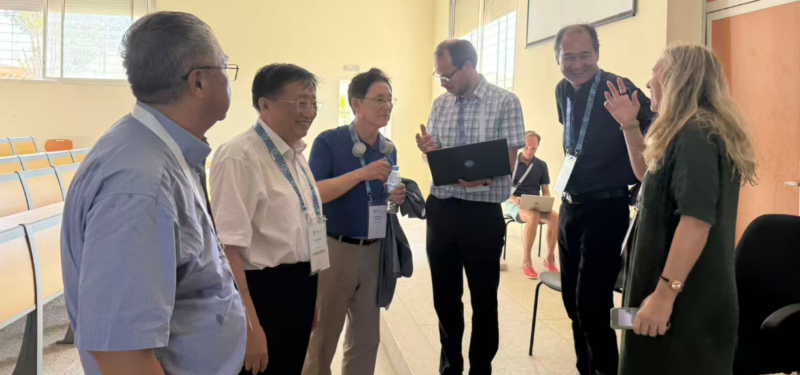

On 20 December 2025, a delegation led by Professor Zhang Guanzi, Director of the National Academy of Chinese Modernization (NACM), Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), paid a formal visit to the Global China Academy (GCA) for academic exchange.

The delegation included Professor Zhang Guanzi (legal anthropology; modernization studies; traditional Chinese legal culture); Professor Han Keqing, Senior Research Fellow and Director of the Research Office (social security; social policy; social welfare; social development and modernization); Associate Professor Feng Xiying, Deputy Research Fellow and Director of the Research Administration Office (grassroots social governance); Assistant Research Fellow Zhu Tao (migrant population; urbanization; employment policy); Assistant Research Fellow Zhang Wenjun (development sociology; political sociology; rural sociology); and Assistant Research Fellow Zhang Shuwan (volunteer services; social governance; development sociology; labour sociology).

This visit marked an important stop in the delegation’s European academic exchange programme. During the one-day visit to the Global China Academy, in addition to formal academic discussions, the Academy arranged a series of British cultural experiences to support the success of the delegation’s subsequent European visits and to facilitate deeper future collaboration.

Following the academic exchange, Professor Zhang Guanzi presented the Global China Academy with a gift—the emblem of the Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies. This gift embodies a clear intercultural logic. One side of the emblem symbolises historical China, while the other represents modern China. Rather than being placed in simple juxtaposition, the two are integrated within a single symbolic structure, mutually interpreting and complementing one another to form a coherent whole, expressed as a unified “middle” (zhong). What is presented here is not a display of cultural difference, but a dialogue and reconfiguration among different historical forms within the same culture—precisely the defining feature of interculturality.

Subsequently, the seal stone presented by Director Han Keqing constituted a typical cross-cultural object. In terms of material, craftsmanship, function, and symbolic meaning, seal stones are deeply rooted in the Chinese literati tradition. When brought from China to the UK and displayed on the shelves of the Fellows’ House, the object was not transformed into part of British culture; instead, it was viewed and understood explicitly as a representative of Chinese culture. What is manifested here is cultural juxtaposition rather than fusion—an instance of “culture being carried and displayed” in the cross-cultural sense.

At the level of human interaction, the visit and symposium of the Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies delegation itself constituted a typical cross-cultural scenario. During the exchange, both the Chinese and British sides maintained clear cultural identities, academic traditions, and institutional backgrounds, seeking mutual understanding through presentation, listening, and comparison. The core of the interaction was not the immediate production of new shared cultural meanings, but rather the recognition of differences and an understanding of the cultural systems from which each side originated. In this sense, the interaction belongs to cross-cultural practice.

At the Fellows’ Home, the delegation toured the Chinese- and English-language books and journals published by Global Century Press, held discussions with Professor Xiangqun Chang, President of the Global China Academy, and shared a traditional British lunch. As Christmas was approaching, the dessert session took the form of an open party, further extending a relaxed yet continuous atmosphere of exchange. This cross-cultural experience did not occur in a single setting, but unfolded through a sequence of highly concrete activities. Conversations began at the Fellows’ House over Chinese tea; continued at lunch with sparkling wine and white wine; and moved on to coffee afterward, with discussions uninterrupted by changes in drinks or venues.

In the afternoon, following the Academy’s long-standing tradition, visiting scholars participated in a “walking–dialogue–dining” programme. This visit followed the sixth route, leading to Brocket Hall, located in Hertfordshire, England. Brocket Hall is a manor of significant political and historical symbolism, having served as the residence of two British Prime Ministers, Lord Melbourne and Lord Palmerston. In the mid-nineteenth century, Palmerston, as a central decision-maker in British foreign policy, led a hardline approach toward China around the time of the First Opium War. His policies profoundly shaped modern Chinese history and the long-term political and cultural imagination of China in the Western world. The Opium War thus became a pivotal historical event that altered China’s trajectory and reshaped the global order, holding particular significance for the Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies. As Christmas—a time of family reunion in Western societies—approached, the delegation experienced the festive atmosphere within Brocket Hall.

A delegation was guided by Mr David Liu, Exactive Manager of GCA, through Brocket Hall, an activity that constituted a tipical intercultural practice. As the former residence of two British Prime Ministers, this British historical space was reinterpreted through the participation of Chinese scholars. When discussions focused on Palmerston’s role in the First Opium War and its implications for Sino-British relations and the nineteenth-century international order, British and Chinese histories were brought into a shared interpretive space. Cultural meanings were renegotiated through face-to-face historical dialogue. Symbolically, Palmerston’s role associated with Brocket Hall is often regarded as marking the point at which China was compelled to enter the modern world system. The Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies takes this historical rupture as a starting point for reflection, systematically examining how China has sought its own path of modernization within the global system.

After touring the residence, the group walked through the estate. Situated along the River Lea, the classical architecture, gardens, and water features together form a landscape where British political history and cultural scenery intersect. Today, Brocket Hall serves as a venue for international conferences and higher education exchange, carrying new public functions upon its historical foundations. The Global China Academy has long used this site as a node for academic visits and walking dialogues, transforming historical settings into spaces for reflecting on global order, institutional change, and civilizational interaction.

Walking through the Brocket Hall estate while observing the architecture and landscape, the group later rested at the Club House with hot chocolate. In the evening, the delegation proceeded to a riverside restaurant in County Hall, facing Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament, for dinner. The evening began with Chinese cuisine, tea, water, and alcohol, followed by a walk through the city at night. Throughout the day, there was no moment in which only a single activity took place: conversations continued while walking, while observing buildings, and while dining or drinking. Different cultural foods, beverages, and spaces appeared in succession, each maintaining its distinct form, while participants continuously moved between and adapted to these cultural contexts. This repeated experience of transition itself constitutes cross-cultural practice.

Later, I accompanied the delegation on a walking tour of central London at night, following the route from Westminster Bridge to Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly Circus, Regent Street, and Bond Street. These walking exchanges further deepened the delegation’s direct understanding of London’s urban space, historical culture, and contemporary social life.

At a kiosk in Trafalgar Square, a rotating indoor hanging ornament featuring a yin–yang (taiji) motif caught our attention. This object provided a vivid illustration for our discussion of how transcultural concepts can be incorporated into research on Chinese modernization. The ornament, manufactured in Italy and revealing a taiji form through rotation, is not a traditional Chinese artifact, nor does it require knowledge of Chinese philosophy or yin–yang theory. Its design language, materials, and production system are clearly globalized. Yet the balance, movement, and symmetry produced through rotation can be directly perceived by people from different cultural backgrounds. This form of expression, no longer belonging to a single culture, exemplifies transculturality.

During our evening walk along New Bond Street, we similarly experienced a transcultural state. A French friend immediately sensed an aesthetic quality that was “both French and already transformed within the British context,” without any need for explanation. Here, cultural characteristics were not identified through national knowledge, but perceived intuitively, indicating that cultural meanings had already been transformed and shared within urban space and everyday experience.

In sum, the exchanges and shared activities of the Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies delegation naturally traversed three distinct yet related cultural forms: cross-cultural, intercultural, and transcultural. Through reflection on specific gifts, spaces, and human interactions, these concepts no longer remain at an abstract theoretical level, but can be clearly distinguished, concretely understood, and deeply internalized through lived experience.

Cross-cultural refers to situations in which distinct cultures, with clear boundaries, are brought into the same time or space for contact, experience, or comparison. At this level, cultures do not undergo structural integration; the focus lies on recognizing differences and understanding origins while respecting cultural boundaries.

Intercultural refers to interactions among different cultures, or among different historical forms within the same culture, in specific contexts, where meaning is negotiated and reconstructed through dialogue, interpretation, and shared experience.

Transcultural refers to forms, values, or modes of perception that have partially or fully detached from their original cultural origins and become experiences that can be directly shared across cultural backgrounds.

Whether at the level of objects (gifts or food) or at the level of human interaction (various forms of behaviour), viewing these three cultural forms together reveals a clear practical pathway: recognizing differences through cross-cultural encounters, engaging in dialogue through intercultural interaction, and sharing meaning through transcultural experience. Through reflection on concrete gifts, spaces, and actions, these cultural concepts can be clearly distinguished, understood, and deeply grasped within lived practice.

This pathway—from practice, through comparison and reflection, to conceptual clarification—also offers an important insight for research on Chinese modernization: modernization is not the transplantation or simple comparison of a single model, but a process continuously understood, adjusted, and reconfigured through sustained interaction among diverse cultural forms.