全球中国学术学院与中国社科院中国式现代化研究院代表团开展学术交流与参访活动

2025年12月20日,中国社会科学院中国式现代化研究院院长张冠梓一行到访全球中国学术学院进行正式交流。代表团成员包括院长张冠梓研究员(法律人类学;现代化研究;中国传统法律文化)、韩克庆研究员 / 研究室主任(社会保障;社会政策;社会福利;社会发展与现代化)、冯希莹副研究员 / 科研办公室主任(基层社会治理)、朱涛助理研究员(流动人口;城市化;就业政策)、张文军助理研究员(发展社会学;政治社会学;农村社会学)和张书婉助理研究员(志愿服务;社会治理;发展社会学;劳动社会学)。

此行是代表团欧洲学术交流的重要一站。在对全球中国学术学院为期一天的访问中,除正式学术交流外,学术学院还为其安排了多项英国文化体验活动,以助力后续欧洲访问的顺利开展及未来合作的深化。

在学术交流结束后,张冠梓院长向学术学院赠送了一件礼品——中国式现代化研究院院徽。这一礼品体现了鲜明的际文化 / 互文化 intercultural 逻辑。作品中一侧象征历史中国,另一侧象征现代中国,两者并非简单并列,而是在同一象征结构中相互解释、相互补充,共同构成一个完整的“中”。这里呈现的不是文化差异的展示,而是文化内部不同历史形态之间的对话与重组,这正是际文化的核心特征。

随后,韩克庆主任赠送的印石礼品则是一个典型的跨文化 cross-cultural 物件。印石在材料、工艺、功能与象征意义上深深植根于中国文人传统。当它被从中国带到英国,并陈列在院士之家的展示架上时,并未被重新塑造成英国文化的一部分,而是作为“中国文化代表”被观看和理解。这里呈现的是文化的并置与对照,而非融合,体现的是跨文化意义上的“文化被携带与展示”。

从人的层面看,中国式现代化研究院代表团的来访与座谈,本身就是一个典型的跨文化场景。中英双方在交流中各自保持清晰的文化身份、学术传统与制度背景,通过介绍、倾听与比较来相互理解。交流的核心并不在于当场生成新的共同文化意义,而在于确认差异、理解彼此来自何种文化体系,因此属于跨文化层面的实践。

在院士之家,访问团参观了环球世纪出版社出版的中英文图书与期刊,并与学术学院院长常向群教授进行了座谈,并共进英式午餐。由于临近圣诞节,正餐后的甜点环节以开放式 party 的形式进行,进一步延续了轻松而持续的交流氛围。这种跨文化经验并非发生在单一场合,而是在一连串非常具体的活动中展开。交流从院士之家开始,边喝中国茶边交谈;午餐时饮汽酒与白葡萄酒,餐后又转至咖啡,讨论并未因饮品或场合的变化而中断。

按照全球中国学术学院的传统安排,来访学者通常会参加“徒步——对话——餐饮”相结合的交流活动(学院共设计有七条不同路线)。本次访问涉及其中的第一与第六条路线,午餐后代表团前往位于英国赫特福德郡的布罗克特庄园 Brocket Hall 进行徒步交流。当日下午,在全球中国学术学院执行经理刘大全先生的带领下,代表团参观了布罗克特庄园。

布罗克特庄园是一处具有重要政治与历史象征意义的庄园建筑,曾先后为两位英国首相——墨尔本勋爵 Lord Melbourne 与 帕默斯顿勋爵 Lord Palmerston——的故居。19世纪中叶,帕默斯顿作为英国外交政策的核心决策者之一,在第一次鸦片战争前后主导了对华强硬路线,其政策不仅深刻影响了中国近代历史进程,也塑造了西方世界对中国的长期政治与文化想象。鸦片战争由此成为一个改变中国命运、并重塑全球秩序的重要历史节点,对中国式现代化研究具有特殊意义。临近圣诞节这一西方社会阖家团圆、亲友相聚的重要时刻,张冠梓院长一行在布罗克特庄园中也切身感受到了这种节日氛围。

这一参访过程构成了一个典型的际文化 intercultural 实践。作为英国两位首相的历史居所,这一英国政治史空间在中国学者的参与下被重新解读。当讨论聚焦于帕默斯顿在第一次鸦片战争中的角色,以及其政策对中英关系与19世纪国际秩序的影响时,英国历史与中国历史被置于同一理解现场,文化意义正是在这种面对面的历史对话中被重新认识与协商。尤具象征意义的是,布罗克特庄园所关联的帕默斯顿,常被视为中国被迫进入现代世界体系的历史起点;而中国社会科学院中国式现代化研究院,正是以这一历史断裂为反思起点,系统研究中国如何在全球体系中探索并形成自身的现代化道路。

参观完官邸后,便在庄园徒步。该庄园坐落于利河 River Lea 河畔,新古典建筑和潘恩桥、园林与水系共同构成英国政治史与景观文化交织的空间。今日的 Brocket Hall 已成为国际会议与高等教育交流的重要场所,在历史沉淀之上承载新的公共功能。全球中国学术院长期将此地作为学术访问与徒步交流的节点之一,使历史现场成为反思全球秩序、制度变迁与文明互动的对话空间。

在布罗克特庄园中,代表团一边徒步一边观赏建筑与景观,在行走中继续交流与讨论。行程结束后,大家在庄园内的高尔夫会所 Club House 稍作休息,围坐饮用热巧克力。此时的交流不再以正式发言为主,而是在轻松的节奏中延续白天关于历史、制度与现代化议题的讨论,使学术对话自然地嵌入身体经验与场景转换之中。

傍晚,前往坐落在老市政厅County Hall的、面对大笨钟和议会大厦的临江宴继续晚餐聚叙。先是吃中餐,喝茶、水,酒,之后再出门步行,看夜里的城市。晚餐后我们徒步考察了伦敦市区夜景,路线为威斯敏斯特桥—特拉法加广场—皮卡迪利广场—摄政街—邦德街。在步行交流中进一步加深了对伦敦城市空间、历史文化与当代社会生活的直观认识。

整天并没有哪一个时刻是“只在做一件事”的:走路时在交谈,看建筑时在讨论,吃饭和饮酒时也在交流。不同文化的食物、饮品与空间轮流出现,但始终保持各自清晰的形态,人不断在这些文化之间移动与适应,这种反复经历的切换本身,就是跨文化实践。

值得一提的是,在特拉法加广场的售货亭中,一个室内旋转的阴阳八卦挂饰引起了我们的注意,这一物件为我们讨论如何在中国式现代化研究中引入转文化 / 超文化transcultural 概念提供了生动注释。这件意大利制造、旋转后呈现太极形态的挂饰,并非中国传统器物,也不要求使用者理解中国哲学或阴阳学说,其设计语言、材料与生产体系本身具有明显的全球化特征。但通过旋转所呈现的平衡、流动与对称感,却能够被不同文化背景的人直接感知,这种已不再从属于单一文化的形式语言,正是转文化的体现。

在 新邦德街 New Bond Street 的夜间漫步中,我们同样体验到了转文化状态。我们共同的来自法国的朋友,无需任何解释,便能立刻感受到一种“既是法国、又已在英国语境中转化”的审美气质。这里的文化特征并非通过国别知识被识别,而是以直觉方式被感受到,显示出文化意义已经在城市空间与日常经验中完成转化并被共享。

总之,中国式现代化研究院代表团的交流与共同活动讨论的主题,事实上自然地贯穿了三种不同但相关的文化形态:跨文化 cross-cultural 、际文化 intercultural 与转文化 / 超文化 transcultural。通过回顾具体礼品、空间与人的行为,这三种概念不再停留在抽象理论层面,而是可以被清晰地区分、具体理解,并在实践经验中加深印象。

- 跨文化cross-cultural指不同文化作为彼此可区分、边界清晰的整体,被带入同一时间或空间中进行接触、体验或比较。在这一层面,文化并不发生结构性融合,其重点在于认识差异、理解来源,并在尊重文化边界的前提下进行交流。

- 际文化 / 互文化 Inter culture指不同文化,或同一文化在不同历史阶段的形态,在具体情境中发生互动,通过对话、解释与共同经验来协商和重构意义。在这一层面,文化不再只是并列存在,而是进入关系之中。

- 转文化 / 超文化Transculture指某些形式、价值或感知方式已经部分或完全脱离其原始文化出处,成为不同文化背景的人可以直接共享的经验。在这一层面,文化不再主要依赖身份、知识或解释,而是通过直觉与感受被理解。

无论在物的层面(礼品或餐饮),还是在人的层面(在不同场景的不同的行为),将这三种文化形态放在一起回看,我们的交流呈现出一条清晰的实践路径:在跨文化中识别差异,在际文化中展开对话,在转文化中共享意义。通过对具体礼品、空间与人的行为进行回顾,这三种文化概念得以被清楚地区分、理解,并在真实经验中加深印象。

这一由实践出发、经由比较与反思而逐步清晰的路径,也为中国式现代化研究提供了一种重要启示:现代化并非单一模式的移植或对照,而是在不同文化形态持续互动中,被不断理解、调整与重构的过程。

Global China Academy and the National Academy of Chinese Modernization (NACM) at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Conduct Academic Exchanges and Study Visits

On 20 December 2025, a delegation led by Professor Zhang Guanzi, Director of the National Academy of Chinese Modernization (NACM), Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), paid a formal visit to the Global China Academy (GCA) for academic exchange.

The delegation included Professor Zhang Guanzi (legal anthropology; modernization studies; traditional Chinese legal culture); Professor Han Keqing, Senior Research Fellow and Director of the Research Office (social security; social policy; social welfare; social development and modernization); Associate Professor Feng Xiying, Deputy Research Fellow and Director of the Research Administration Office (grassroots social governance); Assistant Research Fellow Zhu Tao (migrant population; urbanization; employment policy); Assistant Research Fellow Zhang Wenjun (development sociology; political sociology; rural sociology); and Assistant Research Fellow Zhang Shuwan (volunteer services; social governance; development sociology; labour sociology).

This visit marked an important stop in the delegation’s European academic exchange programme. During the one-day visit to the Global China Academy, in addition to formal academic discussions, the Academy arranged a series of British cultural experiences to support the success of the delegation’s subsequent European visits and to facilitate deeper future collaboration.

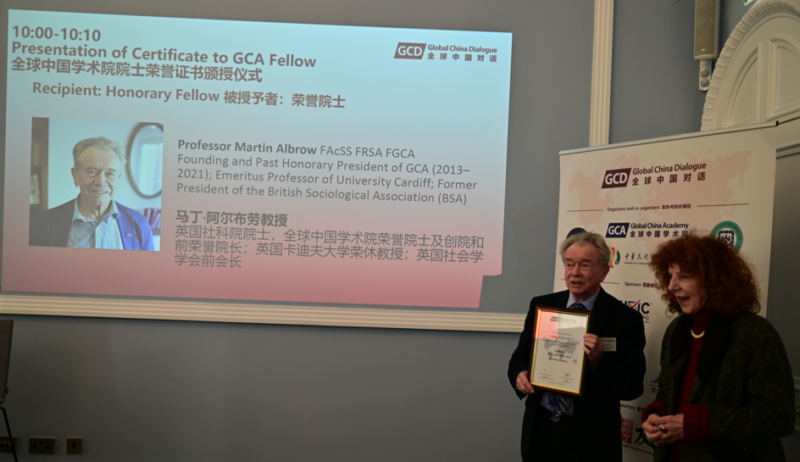

Following the academic exchange, Professor Zhang Guanzi presented the Global China Academy with a gift—the emblem of the Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies. This gift embodies a clear intercultural logic. One side of the emblem symbolises historical China, while the other represents modern China. Rather than being placed in simple juxtaposition, the two are integrated within a single symbolic structure, mutually interpreting and complementing one another to form a coherent whole, expressed as a unified “middle” (zhong). What is presented here is not a display of cultural difference, but a dialogue and reconfiguration among different historical forms within the same culture—precisely the defining feature of interculturality.

Subsequently, the seal stone presented by Director Han Keqing constituted a typical cross-cultural object. In terms of material, craftsmanship, function, and symbolic meaning, seal stones are deeply rooted in the Chinese literati tradition. When brought from China to the UK and displayed on the shelves of the Fellows’ House, the object was not transformed into part of British culture; instead, it was viewed and understood explicitly as a representative of Chinese culture. What is manifested here is cultural juxtaposition rather than fusion—an instance of “culture being carried and displayed” in the cross-cultural sense.

At the level of human interaction, the visit and symposium of the Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies delegation itself constituted a typical cross-cultural scenario. During the exchange, both the Chinese and British sides maintained clear cultural identities, academic traditions, and institutional backgrounds, seeking mutual understanding through presentation, listening, and comparison. The core of the interaction was not the immediate production of new shared cultural meanings, but rather the recognition of differences and an understanding of the cultural systems from which each side originated. In this sense, the interaction belongs to cross-cultural practice.

At the Fellows’ Home, the delegation toured the Chinese- and English-language books and journals published by Global Century Press, held discussions with Professor Xiangqun Chang, President of the Global China Academy, and shared a traditional British lunch. As Christmas was approaching, the dessert session took the form of an open party, further extending a relaxed yet continuous atmosphere of exchange. This cross-cultural experience did not occur in a single setting, but unfolded through a sequence of highly concrete activities. Conversations began at the Fellows’ House over Chinese tea; continued at lunch with sparkling wine and white wine; and moved on to coffee afterward, with discussions uninterrupted by changes in drinks or venues.

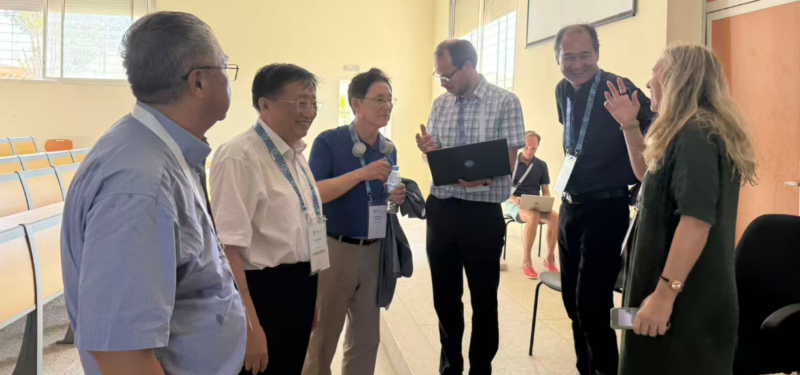

In the afternoon, following the Academy’s long-standing tradition, visiting scholars participated in a “walking–dialogue–dining” programme. This visit followed the sixth route, leading to Brocket Hall, located in Hertfordshire, England. Brocket Hall is a manor of significant political and historical symbolism, having served as the residence of two British Prime Ministers, Lord Melbourne and Lord Palmerston. In the mid-nineteenth century, Palmerston, as a central decision-maker in British foreign policy, led a hardline approach toward China around the time of the First Opium War. His policies profoundly shaped modern Chinese history and the long-term political and cultural imagination of China in the Western world. The Opium War thus became a pivotal historical event that altered China’s trajectory and reshaped the global order, holding particular significance for the Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies. As Christmas—a time of family reunion in Western societies—approached, the delegation experienced the festive atmosphere within Brocket Hall.

A delegation was guided by Mr David Liu, Exactive Manager of GCA, through Brocket Hall, an activity that constituted a tipical intercultural practice. As the former residence of two British Prime Ministers, this British historical space was reinterpreted through the participation of Chinese scholars. When discussions focused on Palmerston’s role in the First Opium War and its implications for Sino-British relations and the nineteenth-century international order, British and Chinese histories were brought into a shared interpretive space. Cultural meanings were renegotiated through face-to-face historical dialogue. Symbolically, Palmerston’s role associated with Brocket Hall is often regarded as marking the point at which China was compelled to enter the modern world system. The Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies takes this historical rupture as a starting point for reflection, systematically examining how China has sought its own path of modernization within the global system.

After touring the residence, the group walked through the estate. Situated along the River Lea, the classical architecture, gardens, and water features together form a landscape where British political history and cultural scenery intersect. Today, Brocket Hall serves as a venue for international conferences and higher education exchange, carrying new public functions upon its historical foundations. The Global China Academy has long used this site as a node for academic visits and walking dialogues, transforming historical settings into spaces for reflecting on global order, institutional change, and civilizational interaction.

Walking through the Brocket Hall estate while observing the architecture and landscape, the group later rested at the Club House with hot chocolate. In the evening, the delegation proceeded to a riverside restaurant in County Hall, facing Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament, for dinner. The evening began with Chinese cuisine, tea, water, and alcohol, followed by a walk through the city at night. Throughout the day, there was no moment in which only a single activity took place: conversations continued while walking, while observing buildings, and while dining or drinking. Different cultural foods, beverages, and spaces appeared in succession, each maintaining its distinct form, while participants continuously moved between and adapted to these cultural contexts. This repeated experience of transition itself constitutes cross-cultural practice.

Later, I accompanied the delegation on a walking tour of central London at night, following the route from Westminster Bridge to Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly Circus, Regent Street, and Bond Street. These walking exchanges further deepened the delegation’s direct understanding of London’s urban space, historical culture, and contemporary social life.

At a kiosk in Trafalgar Square, a rotating indoor hanging ornament featuring a yin–yang (taiji) motif caught our attention. This object provided a vivid illustration for our discussion of how transcultural concepts can be incorporated into research on Chinese modernization. The ornament, manufactured in Italy and revealing a taiji form through rotation, is not a traditional Chinese artifact, nor does it require knowledge of Chinese philosophy or yin–yang theory. Its design language, materials, and production system are clearly globalized. Yet the balance, movement, and symmetry produced through rotation can be directly perceived by people from different cultural backgrounds. This form of expression, no longer belonging to a single culture, exemplifies transculturality.

During our evening walk along New Bond Street, we similarly experienced a transcultural state. A French friend immediately sensed an aesthetic quality that was “both French and already transformed within the British context,” without any need for explanation. Here, cultural characteristics were not identified through national knowledge, but perceived intuitively, indicating that cultural meanings had already been transformed and shared within urban space and everyday experience.

In sum, the exchanges and shared activities of the Institute of Chinese Modernization Studies delegation naturally traversed three distinct yet related cultural forms: cross-cultural, intercultural, and transcultural. Through reflection on specific gifts, spaces, and human interactions, these concepts no longer remain at an abstract theoretical level, but can be clearly distinguished, concretely understood, and deeply internalized through lived experience.

Cross-cultural refers to situations in which distinct cultures, with clear boundaries, are brought into the same time or space for contact, experience, or comparison. At this level, cultures do not undergo structural integration; the focus lies on recognizing differences and understanding origins while respecting cultural boundaries.

Intercultural refers to interactions among different cultures, or among different historical forms within the same culture, in specific contexts, where meaning is negotiated and reconstructed through dialogue, interpretation, and shared experience.

Transcultural refers to forms, values, or modes of perception that have partially or fully detached from their original cultural origins and become experiences that can be directly shared across cultural backgrounds.

Whether at the level of objects (gifts or food) or at the level of human interaction (various forms of behaviour), viewing these three cultural forms together reveals a clear practical pathway: recognizing differences through cross-cultural encounters, engaging in dialogue through intercultural interaction, and sharing meaning through transcultural experience. Through reflection on concrete gifts, spaces, and actions, these cultural concepts can be clearly distinguished, understood, and deeply grasped within lived practice.

This pathway—from practice, through comparison and reflection, to conceptual clarification—also offers an important insight for research on Chinese modernization: modernization is not the transplantation or simple comparison of a single model, but a process continuously understood, adjusted, and reconfigured through sustained interaction among diverse cultural forms.