Since my first visit to Tongji University more than a decade ago, I have attended many meetings and academic events there, yet never truly walked through the campus. Compared with Peking University, Tsinghua University, Wuhan University, and Xiamen University—institutions celebrated for their scholarly traditions and scenic campuses—Tongji’s campus had not particularly drawn my attention. However, my visit to two Tongji campuses on 26–27 February 2025 completely changed this perception.

Tongji University’s main campus is located on Siping Road, with additional campuses at South Campus, Zhangwu, Jiading, Huxi, and Hubei. This visit was hosted by the College of Arts and Media, primarily based at the Jiading Campus, the Chinese partner institution for the 9th Global China Dialogue (GCD9). Accompanied by doctoral student GAO Yuan, I was able to walk through the Siping Road Campus and, for the first time, understand through bodily experience the relationship between the name Tongji and the campus space itself.

We all know that Tongji means “crossing the river together in the same boat,” and that the university originated over a century ago as a Sino–German medical school. Yet it was only by walking through the campus that I realised Tongji truly has water. These waterways are not symbolic landscaping features but historical continuations of the natural rivers and canals of the Jiangnan region. Preserved in campus planning and enhanced through dredging and bank reinforcement, they form walkable and perceptible spatial networks together with buildings, bridges, and pathways. As part of Shanghai’s local river system, they flow eastward or southward, eventually joining the Huangpu River and the Yangtze estuary, embedding the campus within a wider urban and regional geography.

In contrast to the waterways, bamboo groves are mainly found around the early campus buildings, particularly the quiet grove near Sanhao Dock. This area evokes a classical atmosphere that resonates with traditional Chinese garden aesthetics, forming a subtle dialogue with the surrounding modern architecture. These garden spaces are often regarded as embodiments of Tongji’s humanistic spirit—places where faculty and students walk, pause, and sense the layered presence of nature and campus history. Here, the campus becomes not merely a functional educational space, but a lived, immersive environment.

In the past, the most prominent image of Tongji for me was the Mao Zedong statue on campus—a historical and political landmark anchoring a specific era and memory. This time, however, I encountered another sculpture: a contemporary public artwork composed of three figures pulling and supporting one another as they move forward together. There is no hierarchy among them; strength emerges through mutual reliance, forming a dynamic, collective whole. Its mirrored stainless-steel surface reflects buildings, trees, and passers-by, allowing the sculpture to transform continuously with light and time.

At dusk, our walking discussion naturally paused in front of the sculpture. As twilight and artificial light flowed across its metallic surface, memories of the 9th Global China Dialogue (GCD9) held here last November on “AI Governance,” and the subsequent campus visit and roundtable at the College of Arts and Media, seemed to converge into a single, perceptible experience. At that moment, “crossing the river together in the same boat” ceased to be merely a university name or slogan; it became a visible, experiential form of collective action—a public spirit continually generated through collaboration, integration, and shared responsibility.

It was during this walk that I gradually realised Tongji’s campus does not impress through scenery alone, but through the cooperative spirit and engineering rationality embedded in its spaces. Water, bamboo groves, architecture, and sculpture together weave a spatial order that integrates nature, history, and contemporary academic life, giving the name Tongji renewed, tangible meaning through everyday movement and experience.

On the morning of 27 February, I visited the Jiading Campus of the College of Arts and Media at Tongji University. The visit began with an interview conducted by Professor Wang Xin, Head of the Department of Communication. The interview, consisting of 12 questions, explored the transcultural significance of li (ritual/propriety) and exchange, focusing on how the Chinese tradition of li shang wanglai (ritualised reciprocity) can be translated and practised across different civilisations, everyday interactions, and international exchanges, and how it might contribute to contemporary public relations, social trust, and global communication. This was my second interview with Professor Wang; the first was published in Intercultural Communication Studies (Vol. 5, 2022) under the title “Transculturality in Global Perspective: Concepts, Practices, and Production — A Dialogue with Professor Xiangqun Chang.”

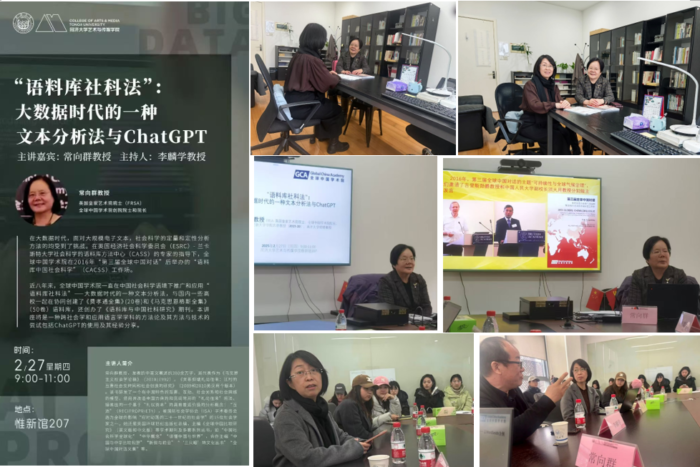

The central event of the morning was my public lecture, “Corpus-Based Social Science: A Text Analysis Method for the Big Data Era and ChatGPT.” The lecture addressed key methodological challenges facing social sciences in the age of big data, where traditional quantitative and qualitative approaches struggle to cope with massive electronic text corpora. The method introduced draws on my training at the Centre for Corpus Approaches to Social Science (CASS) at Lancaster University, supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). Following the 3rd Global China Dialogue in 2016, the Global China Academy launched the “Corpus Approaches to Chinese Social Science” (CACSS) initiative, which has since promoted and applied corpus-based social science methods within Chinese research contexts.

Over the past eight years, in collaboration with several Chinese universities, we have built the Collected Works of Fei Xiaotong (20 volumes) corpus and the Collected Works of Marx and Engels (50 volumes) corpus, and founded the journal Corpus and Chinese Social Science Research, contributing to the institutionalisation of this methodological approach. The lecture presented a framework bridging sociology and applied linguistics, and shared practical experiences using ChatGPT in corpus analysis, research collaboration, and knowledge production, prompting lively discussion among faculty and students.

The lecture was chaired by Professor Wang Xin, with active participation from students and staff. Professor Li Linxue, Dean of the College of Arts and Media, offered concluding remarks, responding to the lecture from perspectives of methodology, knowledge production, and public communication, and proposing future collaboration. From interview to lecture, from concept to method, the morning’s exchanges outlined a clear pathway for transforming Chinese experience into dialogical knowledge and rebuilding public academic practice in the digital era.

Professor Li is a Fellow of the Global China Academy; Professor Wang is an Associate Fellow; and the College of Arts and Media is an Institutional Fellow. The College has served as the Chinese partner for the 8th Global China Dialogue (GCD8) on Global Health Governance and hosted the 9th Global China Dialogue (GCD9) on Global AI Governance, playing a key role in advancing the Academy’s mission, organising international dialogues, and practising transcultural knowledge production.

After the lecture, Dean Li personally guided me through the Jiading Campus, focusing on Yijia Building, a major work of his design. Walking through the building inside and out, he explained the spatial concepts while responding to my questions about the relationship between details and the whole. The building unfolds in a restrained yet powerful modern architectural language: transparent façades, cascading atria, continuous steps and ramps weave teaching, exchange, and public activities into one coherent spatial system. Large-scale halls, open learning spaces, and flexible performance areas transform the building into a “walkable academy” that continually generates opportunities for interaction. Being guided by the designer himself turned architectural concepts into lived experience—this was not merely a tour, but a deep conversation on how architecture can carry public academic life and respond to contemporary educational and cultural missions through spatial practice.

In the afternoon of 27 February, I visited Fudan University. Previous visits to Fudan Library had been for research, but this time was entirely different. I first toured a special exhibition on Yan’an woodcuts, wartime Sino–foreign exchange, and the political mission of art, focusing on the historical connections between American journalist and diplomat George A. Harlan and Chinese revolutionary culture. Titled Return, the exhibition draws mainly on donations from Harlan’s three children, documenting his journeys into Yan’an and liberated areas and his participation in and recording of revolutionary practice. It highlights the Yan’an Woodcut Movement as a form of art that combined political mobilisation, social education, and cultural enlightenment—an essential medium for communication, solidarity, and documentation under wartime conditions. The section “Woodcuts in Yan’an” vividly demonstrates the deep entanglement of art and social practice, offering a compelling lens for understanding knowledge, art, and public life during the revolutionary era.

Through timelines and maps tracing Harlan’s travels across China, the exhibition interweaves personal experience with the histories of war and revolution. Sections such as “Voices of Individuals” and “Collective Echoes” reveal a transcultural network that continued to resonate during and after the war. Letters, manuscripts, prints, and archival documents transform abstract history into tangible evidence.

The exhibition’s restrained curatorial language—dominated by red, grey, and white—creates a powerful narrative space that draws visitors into a shared memory crossing cultures, politics, and media. It is not only a historical reflection but a contemporary question: how can art assume public responsibility in times of crisis, and how can intellectuals forge genuine connections in a fractured world?

Within the library gallery, this exhibition became a living transcultural experience. Different civilisations, political contexts, and knowledge traditions once formed real networks of cooperation through art and action in moments of crisis. As part of an academic visit, this viewing placed present-day scholarly exchange within a longer historical arc—reminding us that scholarship is not only knowledge production, but also a form of public practice. From Yan’an woodcuts to today’s academic dialogues, art, thought, and public spirit are continually reactivated, making “visiting” itself an act that connects past and future.

The visit continued with a tour of the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences Data at Fudan’s Big Data Research Center. The Contemporary Life Archive founded by Professor Zhang Letian, Founding Chinese President of the Global China Academy, and the Secretariat of the Global Contemporary Life Data Alliance he initiated, are both housed here. We also visited the office of Professor Pan Wuyun, a leading scholar in Chinese linguistics and linguistic anthropology, who has played a pivotal role in building the 21st-Century Chinese Language and Dialect Database and advancing research on cultural transmission and population migration. The library thus serves as a vital base for continued scholarly influence after retirement.

This was followed by a roundtable discussion with: Zhang Jilong, Deputy Director of Fudan Library and Executive Deputy Director of the Institute; Yin Shenqin, Deputy Director of the Institute and Deputy Director of the Shanghai Big Data Laboratory for Scientific Research; and Dr Wang Shunqing, Associate Professor and Director of the Contemporary Life Archive and Secretariat. I introduced the academic resources and publishing system of the Global China Academy and Global Century Press. The team expressed strong interest in data sharing, corpus construction, and the upcoming 11th Global China Dialogue (GCD11) on “Global AI and Data Governance” in December 2026.

Yin Shenqin presented the institute’s database system and vast humanities and social science data resources. Zhang Jilong introduced the 2025 Conference on Intelligent Humanities and Social Sciences to be held on 1 March, themed “AI-Driven Theoretical Innovation and Paradigm Transformation in the Humanities and Social Sciences,” covering topics such as AI4SS social agents and complex systems, AI risk identification and decision-making, AI4H and Chinese civilisation, and AI ethics and governance. Dr Wang discussed potential collaboration with the Global Contemporary Life Data Alliance. Both sides expressed a desire for sustained interaction and deeper cooperation.

This visit not only deepened my understanding of Fudan’s digital humanities and data infrastructure, but also established new academic connections for the Global China Academy in AI, data governance, and transcultural research.

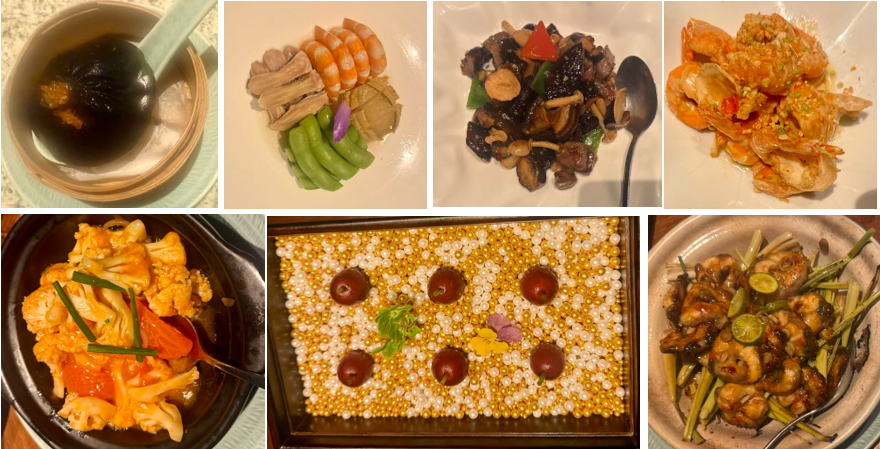

Our exchanges continued over dinner. In China, food often carries layered social meanings, and the innovative Shanghainese–Cantonese fusion cuisine at Longzhuang Xiuchu was particularly memorable. Just as red banners often greet visitors to Chinese universities, this restaurant used bold red slogans as part of its spatial language. Yet unlike traditional restaurants with “No Entry to the Kitchen” signs, its large open kitchen placed cooking at the centre, making every process visible. Slogans such as “Freshly cooked, no pre-made dishes—safety you can see” and “Ingredients have character, cooking has emotion, dishes reflect the person—craftsmanship creates excellence” served not only as quality commitments but as statements about food, labour, and public trust, turning the meal itself into a perceptible form of communication.

The dishes represented a mature style of high-end Chinese cuisine—a contemporary fusion of refined Shanghainese and Cantonese traditions. Plating was restrained and orderly, with precise control of colour and negative space, reflecting clear aesthetic judgement and professional confidence. The sequence of cold dishes, hot dishes, soups, and main courses unfolded with measured rhythm and logic, emphasising natural flavours while building subtle layers through technique rather than visual spectacle. From the textures and flavours, it was evident that the kitchen prioritised heat control and process over heavy sauces: seafood was tender, mushrooms carried wok hei, and soups were clear yet rich—demonstrating solid craftsmanship and fulfilling the promise of visible, honest cooking.

In this atmosphere, conversation was no longer merely verbal continuation; through real cooking, stable quality, and visible labour, a quiet but solid sense of trust was built, allowing dinner itself to become a daily scene in which public spirit found tangible form.